The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has wrapped up its latest five-year reviews of 12 Superfund sites across Massachusetts, offering critical updates on the safety, progress, and ongoing challenges tied to some of the state’s most environmentally sensitive locations. This marks an important checkpoint in the long and complicated journey toward environmental healing for sites once marred by industrial waste, hazardous chemicals, and decades of contamination. Honestly, every time I come across these reports, I’m reminded that while the cleanup may not always grab headlines, the work is vital for the health of people and ecosystems.

Superfund reviews might sound like bureaucratic reports at first glance, but let me tell you, they’re far from just paperwork. These reviews delve deeply into the effectiveness of ongoing remediation efforts and consider if the current measures are safeguarding both human health and the environment as intended. For Massachusetts, the results of these checks are particularly significant: the state has a long history of industrial activity dating back to the 19th century, leaving behind a stark legacy of pollution in certain areas. The 2024 updates indicate whether the cleanup work is on track to meet its long-term goals, or if further action is needed.

WALKING THROUGH THE IMPACTED SITES: A REALITY CHECK

In case you’re wondering, these aren’t just isolated spots tucked away from public view. Superfund sites in Massachusetts range from former industrial plants to landfills, scattered across urban and suburban areas alike. Some of the notable sites reviewed recently include the New Bedford Harbor, infamous for its PCB contamination in marine life, and the Sullivan’s Ledge, a site associated with contaminated soil from industrial waste disposal.

Interestingly, a few of these locations, like the Iron Horse Park in Billerica, straddle a dual identity: parts of the property are in active use for businesses, while sections remain under watch for contamination risks. The EPA’s five-year review isn’t just about saying, “Yep, everything’s fine.” It’s about digging (sometimes literally) into whether the remedies applied so far—like capping landfills or pumping and treating groundwater—are still holding up against time and environmental stressors.

A DEEPER LOOK AT THE EPA’S PROCESS

One of the aspects I personally admire about the five-year review process is its mix of on-ground evaluation and data-driven analysis. The EPA doesn’t just rely on old blueprints or lab results; they actually visit these sites, run inspections, and assess changes in site conditions. They even engage stakeholders, from local community boards to environmental advocacy groups, ensuring no stone is left unturned.

The Massachusetts reviews covered a range of remediation technologies. For example, in Hatheway and Patterson located in Mansfield, ongoing efforts to treat groundwater contamination from industrial solvents were carefully re-evaluated. Similarly, sediment dredging—which you might have heard of from other high-profile Superfund cleanups—has been a major factor in areas like the New Bedford Harbor. These reviews validate whether these methods are minimizing the movement of hazardous materials or if things need a technological upgrade.

CHALLENGES THE EPA FACES IN MOVING FORWARD

While these five-year check-ins are essential, they’re not without challenges. One recurring theme in these reviews is the tension between what’s feasible to clean up completely and what’s practical given budgets and resource constraints. For instance, some sites, particularly those with groundwater issues, are expected to require decades of monitoring and treatment. The process of balancing immediate community needs with long-term solutions is never straightforward. And as you’d expect, natural barriers—like rising groundwater levels or even unexpected climate impacts—can scramble original cleanup timelines.

Another common obstacle is stakeholder engagement. Let’s face it—for many residents living near these sites, the language of “institutional controls” and “remediation technologies” doesn’t always alleviate concerns. Trust-building between communities impacted by lingering contamination, state agencies, and the federal government often takes as much effort as the actual remediation work itself.

HOW MASSACHUSETTS IS LEADING BY EXAMPLE

Here’s the silver lining: despite the challenges, Massachusetts is setting a high bar when it comes to navigating Superfund processes. The state boasts a strong collaboration network among the EPA, MassDEP (Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection), and local municipalities. This makes it easier to carry out multidisciplinary efforts, from monitoring wetlands restoration to ensuring public waterworks remain unaffected.

On a hopeful note, many of these reviewed sites—like the Sullivan’s Ledge—have not just been cleaned up but repurposed for beneficial use. This includes establishing open green spaces, community housing developments, and even renewable energy projects on remediated land. The sum of these outcomes shows that these five-year reviews aren’t just about ticking boxes. They’re about affirming progress and figuring out what the next chapter might look like for some of Massachusetts’ most contaminated, yet resilient, communities.

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS AND SITE CONDITIONS

The findings from the EPA’s latest five-year reviews paint a nuanced picture of progress and lingering challenges across Massachusetts’ Superfund sites. For some locations, the results are downright encouraging—showcasing the advancement of technologies, improved environmental metrics, and even the transformation of once-toxic zones into hubs of community activity. Yet, for others, the reviews act as a sobering reminder that environmental rehabilitation is often a marathon, not a sprint.

Let’s start with the wins. Take New Bedford Harbor, for example, a site historically infamous for its industrial PCB contamination that plagued marine life and sediment for decades. The EPA’s review highlighted that extensive dredging and containment efforts are effectively reducing PCB levels, making headway in restoring the ecological balance. Local fishermen, though still cautious, are slowly regaining trust in these waters. Similarly, Sullivan’s Ledge in New Bedford, once a dumping ground for illegal waste, displays significant improvements. Its capped areas and vegetative covers have turned it into a surprisingly clean and visually pleasant space, though active monitoring continues to ensure contaminants stay locked away beneath the surface.

Meanwhile, at the Iron Horse Park in Billerica, a mixed-use site still under remediation, the reviews confirmed that engineered wastewater treatment systems and landfill capping technologies remain effective. However, they also flagged ‘areas of concern.’ A nearby wetland linked to the site’s drainage pathways is under continuous surveillance, hinting at potential long-term water contamination risks if safeguards fail—a crucial point that highlights the delicate balance between reclamation and vigilance. As for communities surrounding these sites, the EPA regularly commends their collaboration in reporting localized issues that may have otherwise gone unnoticed.

Looking at groundwater-focused sites like Hatheway and Patterson in Mansfield, the findings echo a shared challenge across many Superfund locations: the slow grind of treating large underground plumes of contaminants. Groundwater treatment—for things like volatile organic compounds (VOCs)—is a time-intensive business, and in many cases, these systems are expected to stay operational for decades. That said, the review found no immediate disruptions or deteriorations in the progress of clean-up efforts, though it recommends expanding community outreach to explain the prolonged timeline better.

What’s fascinating about these findings is what they say about the effectiveness of remediation methods. For example:

| Site Name | Primary Concern | Status | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| New Bedford Harbor | PCB contamination | Ongoing dredging efforts | Marine life exposure |

| Sullivan’s Ledge | Soil contamination | Stable under landfill caps | Surface runoff risks |

| Hatheway and Patterson | Groundwater VOCs | Pump-and-treat working | Decades-long timeline |

| Iron Horse Park | Industrial waste | Monitoring effective | Wetland contamination risks |

Of course, not all findings were positive. In some cases, newly emerging concerns have cropped up, demanding additional focus and funding. For example, the steady rise in groundwater levels—a worrying trend linked to regional climate change—was flagged in a few areas. This could potentially influence how contaminants migrate, requiring re-evaluations of previous remediation models. The EPA’s reviews do an excellent job of tackling these evolving dynamics, seeking proactive rather than reactive measures.

What stands out most, at least to me, is how these reports acknowledge that contamination doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Many of these sites intersect with bustling modern-day neighborhoods, meaning the work is never just about soil and sediment; it’s about the people who live nearby. Are kids playing safely in neighborhood parks? Are families using the water supply with peace of mind? These reviews offer a vital layer of transparency, and their findings provide a roadmap for what needs fixing and what’s working as intended. For residents, they signal where vigilance must remain sharp.

One thing’s for sure: the EPA doesn’t sugarcoat its findings. These reports tell a story of resilience, slow but measurable victories, and unflinching honesty when setbacks arise. It’s a mix of good news tempered with the reality that healing decades’ worth of environmental neglect is a monumental task. You can read more about recent Superfund updates from the EPA’s official Superfund page, where they publish detailed site reviews.

FUTURE PLANS AND REMEDIATION STRATEGIES

With every five-year review, the EPA isn’t just taking stock; it’s recalibrating its approach for the next phase of cleanup. The path forward always hinges on a mix of new scientific insights, technological innovations, and the invaluable input of local stakeholders who know these communities like the back of their hand. When I read through the proposed strategies in the 2024 reviews, one message stood out loud and clear: this is a long game, and adaptability is key.

For starters, the EPA is doubling down on technologies that push Superfund cleanups beyond traditional “contain and capping” methods. For instance, in areas like New Bedford Harbor, they’re actively exploring advanced sediment technologies that could accelerate PCB breakdown. These techniques—like reactive capping, where layers are infused with treatment agents—show immense promise in minimizing contaminant spread to marine ecosystems, without the need for as much invasive dredging.

Another headline grabber is groundwater remediation. Let’s talk about Hatheway and Patterson, where the EPA plans to enhance their pump-and-treat systems. How? By integrating emerging bioremediation techniques—essentially, using microorganisms to break down hazardous VOCs in the groundwater. While this might sound like sci-fi, it’s a growing frontier in environmental science that combines eco-friendly methods with measurable results. If successful, this could potentially shave years off the cleanup timeline while cutting down operating costs in the long haul.

On the policy side, there’s also renewed momentum for improving “institutional controls.” These are policies designed to prevent inadvertent exposure to contaminants—think zoning restrictions, public advisories, and bans on digging in certain areas. For sites like Sullivan’s Ledge, the EPA is working with local governments to implement stronger public awareness campaigns and signage to educate nearby communities about the long-term risks lingering beneath the visuals of a seemingly rehabilitated landscape. This isn’t just about keeping people safe; it’s about fostering a sense of transparency and trust.

But it’s not all about shiny tech or municipal partnerships. Climate resilience is another pillar shaping future remediation strategies. Rising sea levels, intensified storms, and fluctuating groundwater tables—all linked to climate change—are pressing concerns for coastal sites like New Bedford Harbor and even inland areas such as Iron Horse Park. Future plans are now integrating predictive climate modeling to ensure today’s cleanups can withstand tomorrow’s environmental shifts. Engineers are reconfiguring drainage systems to handle sudden flooding, reinforcing containment barriers against erosion, and monitoring for faster-than-expected contaminant migration. Honestly, I respect this forward-thinking approach; after all, nothing derails progress faster than Mother Nature refusing to play by the old rulebook.

Beyond the physical site work, there’s also a focus on community-centered solutions. Some of these plans are downright inspiring, like turning formerly contaminated zones into renewable energy hubs. Imagine fields of solar panels thriving on once-toxic soil. In fact, Sullivan’s Ledge has already kickstarted this vision, with solar panel installations generating clean energy, and the EPA hopes to replicate this success across other sites. Similarly, long-term plans for Iron Horse Park include restoring parts of the surrounding wetland, effectively creating green buffers that not only curb contamination spread but support local biodiversity.

Of course, nobody’s claiming this work will be smooth sailing—remediation is riddled with uncertainties. Advances in AI and remote sensing tech are expected to play a large role in navigating these complexities. The EPA is increasingly harnessing machine learning to monitor changes in groundwater quality in real time and to predict long-term contaminant behavior under varying conditions. This predictive capability could eliminate some of the guesswork and make interventions timelier and more precise.

If you’re wondering how this all ties to funding, well, the harsh reality is that the scale of some Superfund projects outstrips current federal budgets. Public-private partnerships may very well be the key to unlocking bold new projects. For example:

- Incentivizing green energy developers to adopt and repurpose remediated sites.

- Collaborating with local businesses to fund maintenance of non-active portions of sprawling sites like Iron Horse Park.

- Increased grant funding tied to innovative remediation techniques.

At the end of the day, there’s no “one-size-fits-all” solution. Each site is like a puzzle with its own unique mix of geographic, chemical, and social challenges. What makes me optimistic, though, is the sheer determination packed into these plans. It’s clear the EPA isn’t just checking boxes; they’re focused on crafting solutions that balance ecological integrity, human health, and economic potential. If this holistic strategy sets a precedent for other states, well, we might just be looking at a national cleanup renaissance.

For those curious to dive deeper into the evolving Superfund landscape, the EPA’s Superfund program page offers excellent resources and detailed updates on remediation technologies, site-specific policies, and long-term visions for recovery.

As the EPA prepares future plans and builds new remediation strategies for Massachusetts’ Superfund sites, it’s clear there’s a meticulous balance between science, community collaboration, and a touch of bold innovation. Let’s break down some of the forward-looking measures and initiatives aiming to tackle the unique environmental challenges these sites pose—and, in some cases, even turn these liabilities into opportunities.

ADVANCED CLEANUP: FROM CAP-AND-CONTAIN TO ACTIVE TREATMENT

The days of simply “covering it up and walking away” are long gone. Modern Superfund strategies emphasize proactive treatment to not just isolate contaminants but actively neutralize them. Take, for instance, the escalating interest in reactive capping technologies for sites like New Bedford Harbor. Instead of the traditional method of sealing contamination beneath a simple isolation layer, reactive caps are embedded with chemical agents designed to capture or break down pollutants over time. It’s like upgrading your area rug into a vacuum cleaner—why just hide the dirt when you can clean it up?

At the Hatheway and Patterson site in Mansfield, bioremediation is taking the stage, with scientists collaborating to leverage natural microorganisms to “eat away” hazardous volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in polluted groundwater. The method is slow, sure, but it offers exceptional returns in terms of long-term efficiency and environmental safety. Plus, it feels almost poetic—nature undoing the damage humans caused. This kind of innovation has broader implications beyond just Superfund sites, proving once again how necessity sparks technological breakthroughs.

TAILORING STRATEGIES TO CLIMATE CHALLENGES

Climate change isn’t just reshaping where and how we live; it’s also rewriting the rules of how contaminant migration behaves. Floodplains are expanding, unpredictable storm patterns are intensifying erosion, and groundwater tables are shifting like never before. For Superfund sites in coastal areas like New Bedford Harbor, the stakes couldn’t be higher. The EPA plans to incorporate predictive climate modeling as a cornerstone of its next-gen strategies. This involves using advanced AI and simulation technologies to predict how rising seas, heavier rainfall, or even drought conditions may alter the stability of existing clean-up efforts.

Furthermore, measures are being introduced to reinforce physical defenses at these sites. Think reinforced landfill caps, improved drainage infrastructure, and secondary containment systems for groundwater plumes. Sites like Iron Horse Park, which already face wetland-related contamination risks, will pilot these methods, testing their durability in the face of unpredictable weather patterns. Some may call it overengineering; I call it forward thinking.

TURNING PROBLEMS INTO OPPORTUNITIES: SUPERFUND REUSE PROJECTS

One element of the remediation plans that genuinely excites me is the growing push to repurpose once-toxic areas into something productive and sustainable. The poster child for this vision might be Sullivan’s Ledge, where a former dumping ground has been transformed into a solar energy farm. Imagine this: clean energy powering nearby neighborhoods, all from a site that—just decades ago—was a no-go zone for humans and nature alike.

The EPA, in partnership with local governments, is eyeing similar projects for other sites. Discussions are underway to explore green infrastructure like urban parks and bird sanctuaries at remediated wetlands. There’s also interest in collaborating with renewable energy developers to install wind or solar farms on capped landfill areas, taking advantage of the large plots of land unfit for traditional development.

This second-life approach doesn’t just benefit the environment but also lifts the communities surrounding these areas. Who wouldn’t want to swap a distant view of decrepit hazards for neatly aligned solar panels or a recreational park buzzing with life?

INSTITUTIONAL CONTROLS AND PUBLIC AWARENESS

The EPA cannot achieve these improvements in isolation; policies and public education efforts play a pivotal role. Enter institutional controls, the overlooked but highly effective set of administrative tools. These controls regulate land-use policies and provide clear guidelines to prevent risky activities, like digging in contaminated zones or sourcing water from restricted groundwater wells. However, the current plans take this a step further—not only reinforcing signage and zoning restrictions but also rolling out digital tools like interactive maps where residents can check contamination zones near their properties in real-time.

On the public engagement front, the EPA is introducing revamped community outreach initiatives. Picture door-to-door campaigns paired with info sessions held at local libraries and schools, ensuring residents are informed about site safety updates. New educational partnerships are forming, too, giving rise to job training programs that teach locals about monitoring technologies and eco-friendly project management—equipping communities with the tools they need to be part of the solution, rather than passive recipients of progress.

ENHANCING MONITORING WITH SMART TECHNOLOGIES

No modern cleanup process is complete without the integration of advanced technology, and the EPA is fully on board. Remote sensing and real-time monitoring systems are being scaled up at nearly all active Superfund sites in Massachusetts. This means drones equipped with thermal cameras and AI systems will routinely patrol sites like Hatheway and Patterson, scanning every nook and cranny for new leaks or irregular shifts in groundwater quality.

What’s more, the EPA has begun experimenting with machine learning algorithms that analyze decades of monitoring data to provide predictive insights. Think of it as having a weather forecast for contaminant movement—knowing that subtle changes in temperature, humidity, or water levels could lead to bigger problems months down the line. These digital overlords are particularly useful for resource-heavy projects like the New Bedford Harbor, where managing an active marine ecosystem continuously collides with decades-old industrial waste.

And let’s not forget funding: harnessing these cutting-edge tools comes with a price tag, but it’s one that advocates (and frankly, I agree) argue is worth every penny. After all, precision monitoring could save millions in emergency interventions later.

- AI-assisted forecasting for groundwater contamination.

- Drone surveillance for erosion and cap integrity.

- Automated sampling of air quality near residential zones.

By creating a high-tech safety net, remediation efforts can shift from reactive “clean-as-you-go” models to proactive strategies that predict and prevent contamination before it spirals out of control. It’s an approach that feels less like damage control and more like future-proofing the land for generations to come.

From leveraging cutting-edge science to embracing community participation and transforming blighted lands into thriving spaces, the EPA’s evolving remediation strategies are as ambitious as they are necessary. It’s a hefty task, no doubt, but progress feels remarkably tangible, and every new plan seems to inch Massachusetts closer to undoing its troublesome environmental legacy. You can learn more about the different technologies and community impacts by visiting the EPA Superfund Program, where they break down these efforts in rich detail.

The intersection of public health, environmental integrity, and community resilience forms the heart of the EPA’s Superfund program. While the technical cleanup of hazardous sites often garners attention, perhaps the most profound and immediate impact of these efforts lies in their effects on local communities and the surrounding environment. And let’s be honest—these impacts are not just about turning polluted soil or water clean again. They’re about renewing hope for people who’ve lived with contamination as a shadow over their lives for decades. It’s equal parts science, policy, and humanity at work.

RESTORING ENVIRONMENTS: FROM TOXIC BACKYARDS TO WELCOME SPACES

First, let’s talk about the ecological legacy. Many Massachusetts Superfund sites—like New Bedford Harbor—were once ecological black holes where nothing could thrive. For decades, industrial pollution smothered aquatic ecosystems, displaced local species, and left behind a barren wasteland of toxic sediments. The EPA’s remediation progress has brought life back to these environments in slow, deliberate steps. Using strategies like dredging and containment, they’ve managed to reduce PCB levels in sediments, helping to restore viable aquatic ecosystems that were once considered lost causes.

But I think what’s even more striking is the transformation of spaces like Sullivan’s Ledge. This site, which once housed illegal waste dumps, has now been remediated to such an extent that it’s repurposed into a solar farm. Imagine looking out your kitchen window and seeing rows of solar panels glistening in the sunlight instead of mounds of debris or fenced-off contaminated zones. These changes are creating tangible enhancements in quality of life—and not just for flora and fauna but for the humans who call these neighborhoods home.

Beyond ecological rehabilitation, there’s also a psychological component. Cleaner environments alleviate the mental toll of living amidst contamination fears. Parents can feel secure as their kids play near restored wetlands or rehabilitated parks. Neighbors begin to reclaim areas once deemed unsafe. There’s something incredibly compelling about seeing polluted lands become spaces for celebration, relaxation, and regeneration.

PUBLIC HEALTH BENEFITS: CLEAN WATER AND SAFER AIR

The public health implications of these environmental turnarounds are monumental. For many of these communities, proximity to a Superfund site wasn’t just a minor inconvenience; it was, quite frankly, a health hazard. In areas with contaminated water tables—like Hatheway and Patterson—families lived under constant warnings to avoid well water consumption due to VOC (volatile organic compound) contamination. Similarly, air pollution from industrial-era waste occasionally affected residents near sites like Iron Horse Park. These weren’t just inconveniences; they were daily realities that impacted everything from infant health to elderly immune systems.

Thanks to the EPA’s five-year reviews and updated remediation strategies, those risks are being mitigated more effectively than ever. Groundwater plumes are being treated at the source, and air quality monitoring has been stepped up to assure communities that carcinogenic or toxic chemicals aren’t seeping or escaping into their living environments. While full healing is a long road—some remedies take decades—improvements in water quality and air safety are being felt more quickly. To give credit where it’s due, these tangible changes represent livelihoods improved, hospitalizations avoided, and communities re-empowered to live without the fear of unseen dangers.

ECONOMIC FACTORS: BAD REPUTATIONS TURNED TO COMMUNITY ASSETS

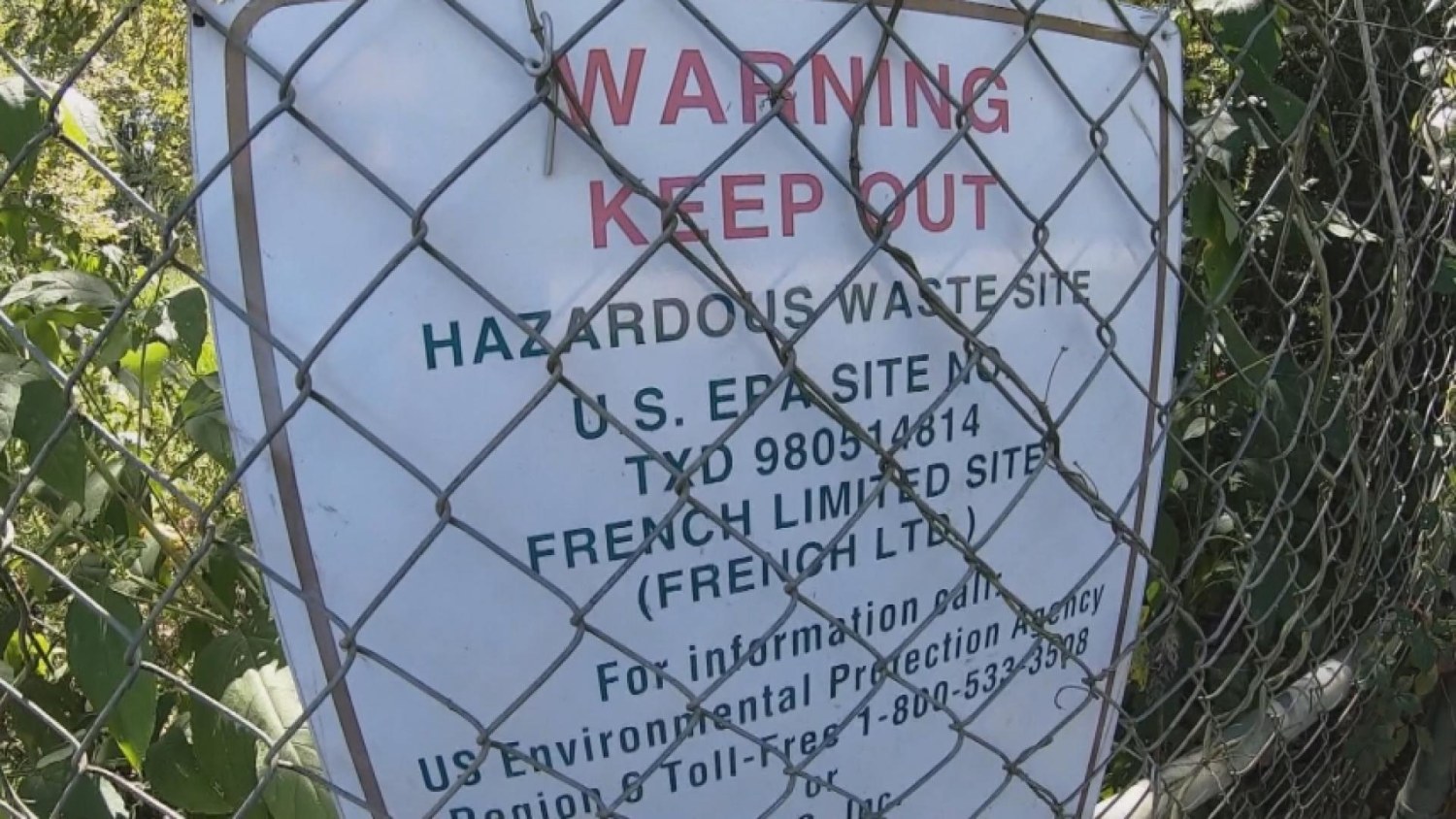

An overlooked, yet massively important, aspect of Superfund success stories lies in their economic ripple effects. Superfund sites are often associated with plummeting property values and dwindling investment in affected towns. After all, who wants to live—or start a business—within throwing distance of a sign that says, “Caution: Contaminated Area”? This stigma has historically left many such areas in an economic rut, stripped of opportunities for renewal.

However, as sites are remediated, impressions change. Take New Bedford Harbor. As PCB levels drop in the water and marine ecosystems revive, the local economy could see boosted tourism and fishing activities long stifled by contamination fears. Similarly, sites like Sullivan’s Ledge are showcasing how formerly unusable lands can be turned into profitable assets. The solar energy farm built there not only provides clean energy but also generates tax revenue and creates local jobs. If further economic-side projects continue sprouting from these efforts, it’s easy to see how the remediation of a Superfund site can become a revitalization springboard for struggling towns.

What’s worth noting is how community involvement feeds into the economic side of things. When residents feel they’re part of the conversation—through public meetings, workshops, or surveys—they’re more likely to envision these sites as future opportunities rather than haunted pasts. Developers, in turn, gain the confidence to invest, paving the way for new infrastructure, businesses, and recreational spaces. The shift here is powerful: from viewing these sites as liabilities to recognizing them as untapped potential.

COMMUNITY TRUST AND ENGAGEMENT: THE HUMAN TOUCH

At the heart of any cleanup effort are the people most affected by it: the residents. Over the years, I’ve covering environmental stories, it’s striking how often I’ve heard locals express frustration over feeling overlooked or ignored during remediation efforts. To the EPA’s credit, that narrative has shifted in recent years. Community engagement has become a crucial pillar in Superfund strategies, and nowhere is that clearer than in Massachusetts.

For example, ongoing reviews now include feedback channels where residents can document observed changes in their surroundings—whether it’s unusual water odors, wildlife behavior, or unexpected erosion. These observations often serve as real-time inputs that supplement scientific data, creating a collaborative approach to monitoring. Beyond that, public information campaigns, like those deployed around Iron Horse Park, are educating families on what remediation work entails and what safeguards are being put in place to guarantee their safety.

One standout example of engagement is the introduction of job training programs for nearby residents. These programs not only provide skills—like environmental monitoring and waste management techniques—but also ensure locals feel invested in the future of their own communities. It’s no silver bullet, but it’s certainly a step toward instilling trust in institutions that have historically struggled to demonstrate sincerity or immediacy in their actions.

COLLABORATIVE SUCCESS: THE ROLE OF LOCAL AND FEDERAL PARTNERSHIPS

Of course, none of this would be as effective without strong partnerships between federal entities like the EPA and local players. Here in Massachusetts, collaboration between the EPA, towns, and the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) has been crucial for building frameworks that fit the unique needs of each site. These partnerships have also ensured quicker responses to emerging challenges like rising groundwater tables linked to climate change.

In the case of sites with active economic use—such as Iron Horse Park, where there’s overlapping industrial activity—municipalities have stepped up to ensure a balance between land use and environmental integrity. This synergy between local and federal forces serves as a reminder that Superfund efforts work best when communities, regulators, and businesses pull in the same direction.

The impact of Superfund cleanups goes far beyond what’s measurable in soil samples or containment reviews. It touches every facet of life in affected areas—economic vitality, daily health, and even the quality of public trust. As challenging as the process may be, seeing progress unfold is like watching a piece of history slowly being rewritten—and, frankly, you don’t always get that kind of inspiration in environmental reporting.

77 Comments

In conclusion, the recent EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in remediation efforts while also underscoring the ongoing challenges that remain. While advancements in cleanup technologies and community involvement have led to improved environmental conditions, the persistence of certain pollutants and the complexity of site conditions continue to pose obstacles. Ongoing collaboration between the EPA, state agencies, and local communities will be essential to ensure the successful resolution of these challenges and to restore affected areas for future generations.

The recent updates from the EPA regarding Massachusetts Superfund sites reflect significant progress in addressing environmental contamination and safeguarding public health. While the efforts have led to successful remediation in various locations, ongoing challenges remain in fully restoring affected areas and ensuring long-term sustainability. Continuous collaboration among federal, state, and local stakeholders will be essential to overcome these obstacles and achieve comprehensive solutions. Overall, the commitment to ongoing monitoring and improvement underscores the importance of vigilance and sustained action in managing Superfund sites for the benefit of Massachusetts communities and the environment.

In conclusion, the recent EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in remediation efforts, showcasing the commitment to restoring these contaminated environments. However, ongoing challenges remain, emphasizing the need for sustained collaboration and resources to address the complexities of cleanup processes. Continued vigilance and community engagement will be essential as stakeholders work towards ensuring the health and safety of local ecosystems and residents.

In conclusion, the recent updates from the EPA regarding Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in addressing environmental contamination and cleaning up affected areas. While these advancements are encouraging, they also underscore the ongoing challenges that remain in ensuring the safety and health of local communities. As stakeholders continue to collaborate and implement solutions, it is essential to maintain momentum and address the lingering issues to secure a cleaner and safer environment for future generations.

In conclusion, the latest EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites reflect significant progress in addressing environmental contamination and rehabilitating affected areas. While advancements have been made in cleanup efforts and community engagement, ongoing challenges remain, including the need for continued funding and completion of remediation processes. As stakeholders work together to overcome these obstacles, the commitment to restoring these sites promises a healthier environment and improved quality of life for residents. Continued vigilance and collaboration will be essential to ensure that these efforts lead to lasting positive outcomes for the communities involved.

In conclusion, the latest EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in the remediation and restoration of contaminated areas, reflecting the commitment to environmental health and community safety. However, ongoing challenges remain, underscoring the need for continued vigilance, funding, and innovative strategies to address complex pollution issues. Collaboration among government agencies, local communities, and stakeholders will be essential to ensure the successful revitalization of these sites and protect public health for future generations.

The latest updates from the EPA regarding Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight both significant progress and persistent challenges in addressing environmental contamination. While efforts to remediate these sites have led to improvements in public health and ecological restoration, ongoing monitoring and community engagement remain crucial. Moving forward, collaboration among federal, state, and local stakeholders will be essential to ensure the effective management of these sites and to overcome the hurdles that still exist in achieving comprehensive, long-term solutions for affected communities.

In conclusion, the latest EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight both substantial progress in remediation efforts and the persistent challenges that remain. While significant strides have been made in cleaning up contaminated areas and protecting public health, ongoing vigilance and resource allocation are crucial to address lingering environmental concerns. The commitment of local communities, state officials, and federal agencies will play a vital role in ensuring that these sites are fully restored and that future risks are mitigated. Continued transparency and collaboration will be essential as stakeholders work together to achieve a cleaner and safer environment for all residents.

In conclusion, the recent EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites indicate significant progress in cleanup and remediation efforts, reflecting a commitment to restoring impacted environments and safeguarding public health. However, ongoing challenges remain, including the need for continued funding, community engagement, and effective management of complex contamination issues. As stakeholders collaborate to address these challenges, the path forward must balance environmental healing with the demands of local communities, ensuring that the successes achieved pave the way for a sustainable and healthier future.

In conclusion, the latest EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight both significant progress in remediation efforts and the persistent challenges that remain. While advancements demonstrate a commitment to restoring contaminated environments and protecting public health, ongoing obstacles emphasize the need for continued vigilance and support. As stakeholders work together to address these issues, the path forward will require sustained investment and community engagement to ensure long-term success in revitalizing affected areas.

In conclusion, the recent EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight both significant progress in remediation efforts and ongoing challenges that need to be addressed. While the advancements demonstrate the effectiveness of environmental policies and community collaboration, persistent contamination and regulatory hurdles remind us of the complexities involved in restoring affected areas. Continued diligence and support are essential to ensure that these sites achieve their full potential for revitalization and public safety.

In conclusion, the EPA’s updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites illustrate a significant commitment to environmental remediation and public health, highlighting both the progress made and the ongoing challenges that remain. While advancements in cleanup efforts and community engagement are encouraging, continued vigilance, funding, and adaptation of strategies will be essential to address the complexities of contamination and ensure lasting restoration of affected areas. Stakeholder collaboration and sustained efforts will be crucial in navigating the path forward, ultimately aiming for a cleaner and healthier environment for all residents.

In conclusion, the recent EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in the cleanup and management of contaminated areas, reflecting a commitment to restoring environmental health and safety. However, these updates also underscore ongoing challenges that need to be addressed, including complex site conditions and the need for sustained funding and community engagement. Continued collaboration among federal, state, and local stakeholders will be essential in overcoming these challenges and ensuring the long-term success of remediation efforts in Massachusetts.

In conclusion, the latest EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in remediation efforts, reflecting a commitment to addressing environmental contamination and enhancing public health. However, ongoing challenges remain, underscoring the need for continued vigilance and collaborative efforts among stakeholders to ensure that these sites are thoroughly rehabilitated. As the state moves forward, it will be essential to maintain momentum and address any lingering issues to protect the environment and the communities that depend on it.

In conclusion, the latest EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in remediation efforts, demonstrating a commitment to improving environmental health and safety in affected communities. However, challenges remain as some sites require continued attention and resources to ensure comprehensive cleanup. Ongoing collaboration between federal, state, and local stakeholders will be essential to address these challenges and achieve lasting solutions for a cleaner, safer environment.

In conclusion, the recent updates from the EPA regarding Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight both significant progress in remediation efforts and the continued challenges that lie ahead. While advancements have been made in addressing environmental contamination and restoring these critical areas, ongoing vigilance and resources are necessary to ensure that these sites are adequately managed and that public health and ecosystems are protected. The commitment to resolving these issues underscores the importance of collaborative efforts between federal, state, and local stakeholders in advancing environmental clean-up and safety initiatives.

In conclusion, the recent EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in addressing environmental contamination and restoring affected areas. However, ongoing challenges remain, necessitating continuous collaboration among federal, state, and local stakeholders to ensure the health and safety of communities. The commitment to rigorous remediation efforts and monitoring will be essential in overcoming these challenges and achieving long-term sustainability. This underscores the importance of vigilance and proactive measures in safeguarding the environment for future generations.

In conclusion, the recent updates from the EPA regarding Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight a significant commitment to environmental restoration and public health. While progress has been made in cleaning up and managing these contaminated areas, ongoing challenges remain that require continued attention and resources. The collaboration between federal, state, and local stakeholders is essential to overcome these obstacles and ensure the safety and well-being of affected communities. Continued vigilance and investment in these efforts will be crucial for achieving lasting environmental improvements and safeguarding public health in Massachusetts.

In conclusion, the recent updates from the EPA on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight both significant progress in remediation efforts and persistent challenges that remain. While strides have been made in cleaning up contaminated areas and restoring communities, ongoing issues such as funding limitations, public health concerns, and the complexity of site-specific conditions continue to pose obstacles. The commitment to addressing these challenges is vital for ensuring the long-term safety and well-being of Massachusetts residents, underscoring the need for collaboration among government agencies, local communities, and environmental organizations.

In conclusion, the recent updates from the EPA regarding Massachusetts Superfund sites reflect a commendable commitment to environmental remediation and public health. While significant progress has been made in addressing contamination and restoring affected areas, ongoing challenges remain that require continued attention and resources. Collaborative efforts among federal, state, and local stakeholders will be crucial in ensuring that these sites are fully revitalized, ultimately contributing to a safer and cleaner environment for all residents. A balanced approach that combines effective cleanup strategies with community involvement will be essential to overcome the hurdles still present in these critical restoration efforts.

In conclusion, the latest EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites reflect significant progress in remediation efforts, showcasing the effectiveness of dedicated environmental management and community engagement. However, ongoing challenges remain, including addressing lingering contamination and securing adequate funding for comprehensive clean-up. These insights underline the importance of continued vigilance and collaboration among stakeholders to ensure a safer, healthier environment for all residents.

In conclusion, the latest EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in mitigating environmental hazards and revitalizing affected communities. However, ongoing challenges remain, including complex contamination issues and the need for sustained funding and stakeholder collaboration. Continuous efforts are essential to ensure the protection of public health and the environment, paving the way for a cleaner and safer future for residents in these impacted areas.

In conclusion, the latest EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in addressing environmental contamination and restoring impacted areas. However, ongoing challenges remain, necessitating continued commitment and collaboration among federal, state, and local stakeholders. As efforts persist to remediate these sites, the importance of addressing both immediate and long-term environmental health concerns remains critical to safeguarding communities and ecosystems in Massachusetts.

In conclusion, the recent updates from the EPA regarding Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight a significant commitment to environmental remediation and public health. While notable progress has been made in addressing contamination and mitigating risks, ongoing challenges remain that require continued attention and resources. The efforts to restore these sites not only reflect a dedication to protecting ecosystems but also demonstrate the importance of community involvement and transparency in the decision-making process. As Massachusetts moves forward, collaboration between government agencies and local stakeholders will be essential for achieving long-term environmental sustainability and ensuring the safety of affected communities.

In conclusion, the recent updates from the EPA regarding Massachusetts Superfund sites reflect a significant commitment to environmental remediation and public health. While progress has been made in cleaning up contaminated areas and reducing risks to communities, ongoing challenges remain that require continued attention and resources. Collaborative efforts among governmental agencies, local stakeholders, and community members will be essential to ensure that these sites are fully restored and that future environmental concerns are effectively addressed. The path forward highlights the importance of sustained engagement and vigilance in the fight for a healthier environment.

In conclusion, the recent updates from the EPA regarding Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in remediation efforts, reflecting a commitment to improving environmental health and mitigating contamination risks. However, ongoing challenges remain, necessitating continued vigilance, funding, and community involvement to ensure that all affected areas achieve complete restoration and safety for residents. The path forward will require collaboration between federal, state, and local stakeholders to address these challenges effectively and sustain the momentum gained in the cleanup efforts.

In conclusion, the recent updates from the EPA regarding Massachusetts Superfund sites reflect significant progress in environmental remediation and community health initiatives. While strides have been made in addressing contamination and restoring affected areas, ongoing challenges remain that necessitate continued vigilance and investment. Collaborative efforts among federal, state, and local entities will be essential to ensure that these sites are effectively managed, with a focus on long-term sustainability and protection of public health. As Massachusetts moves forward, the commitment to transparency and community engagement will play a critical role in overcoming the remaining hurdles in the Superfund programs.

In conclusion, the recent updates from the EPA regarding Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant advancements in remediation efforts and environmental recovery. While progress is evident in the cleanup and management of contaminated areas, ongoing challenges remain, including the need for continued funding, community engagement, and monitoring to ensure long-term safety and sustainability. These updates underscore the importance of persistent efforts and collaborative strategies to address the complex issues associated with hazardous waste sites, ultimately aiming for a healthier environment for all residents.

In conclusion, the recent EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant strides made in environmental remediation and community health improvements while also underscoring the ongoing challenges that persist. While progress in cleaning up contaminated areas reflects a commitment to restoring ecosystems and protecting public health, continued vigilance and resources are necessary to address remaining hazards and ensure long-term sustainability. Collaborative efforts among federal, state, and local stakeholders will be crucial in overcoming these challenges and fostering a cleaner, safer environment for all Massachusetts residents.

In conclusion, the latest EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites underscore significant progress in cleanup efforts and environmental restoration. While advancements have been made in addressing contamination and protecting public health, ongoing challenges remain that necessitate continued vigilance, funding, and community engagement. Balancing redevelopment and ecological integrity will be crucial for sustaining momentum and ensuring a safer, healthier environment for all residents in the affected areas.

In conclusion, while the EPA’s updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites reflect notable progress in addressing environmental contamination and restoring affected areas, the challenges that remain underscore the complexity of the cleanup process. Continuous monitoring, community engagement, and sustained funding will be crucial to ensure that all sites are effectively remediated and that public health is protected. The ongoing efforts highlight the importance of collaboration between government agencies, local communities, and stakeholders in achieving long-term environmental resilience.

In conclusion, the recent EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight both significant progress in remediation efforts and the ongoing challenges that remain. While strides have been made in restoring contaminated areas and protecting public health, the complexities of certain sites continue to demand attention and resources. Ongoing collaboration between federal, state, and local stakeholders will be crucial in ensuring that these efforts not only maintain momentum but also address any emerging concerns, ultimately leading to safer environments for Massachusetts residents.

In conclusion, the recent EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight a mix of significant progress in remediation efforts and the persistent challenges that remain. While advancements in cleanup initiatives demonstrate a commitment to restoring these contaminated areas, ongoing environmental concerns and the complexities of involved remediation processes underscore the need for continued vigilance and investment. Collaborative efforts among federal, state, and local stakeholders will be essential in ensuring that these sites are not only restored but also safeguarded for future generations.

In conclusion, the recent EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in remediation efforts, underscoring the commitment to improving environmental health and safety in impacted communities. However, ongoing challenges remain, necessitating continued collaboration and vigilance to address lingering contamination and ensure a sustainable recovery. It is crucial for stakeholders to remain engaged and proactive in overcoming these obstacles to protect public health and restore the environment effectively.

In conclusion, the latest EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites reflect significant progress in the cleanup and management of these contaminated areas, highlighting the commitment to safeguarding public health and the environment. However, ongoing challenges remain, including the need for continued funding, effective stakeholder engagement, and long-term monitoring to ensure sustainable remediation. Addressing these challenges will be vital to fully realizing the potential of these sites for community revitalization and ecological restoration.

In conclusion, the EPA’s updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites reflect significant advancements in the remediation efforts aimed at addressing environmental contamination. While progress underscores the commitment to restoring affected areas and protecting public health, ongoing challenges highlight the complexities of managing such sites. Continued collaboration among federal, state, and local stakeholders will be crucial to overcoming these hurdles and ensuring the long-term recovery and safety of Massachusetts’ communities and ecosystems.

In conclusion, the EPA’s recent updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in remediation efforts and community engagement. While the advancements demonstrate a commitment to restoring affected areas, ongoing challenges remain, including ensuring long-term sustainability and addressing the needs of impacted communities. Continued collaboration between federal, state, and local agencies will be crucial for overcoming these hurdles and achieving comprehensive environmental recovery.

In conclusion, the EPA’s updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites reflect a significant commitment to environmental remediation, showcasing notable progress in cleanup efforts. However, challenges remain, highlighting the complexity of addressing contamination and ensuring long-term sustainability. Continuous collaboration among federal, state, and local stakeholders will be essential in overcoming these obstacles and protecting public health and the environment. As efforts advance, the dedication to improving these sites serves as a vital reminder of the importance of ongoing environmental stewardship.

In conclusion, the latest EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites reflect significant progress in addressing environmental hazards and remediation efforts. However, ongoing challenges remain, highlighting the need for continued vigilance and innovative solutions to ensure the health and safety of affected communities. As these efforts advance, collaboration among federal, state, and local stakeholders will be crucial in overcoming obstacles and achieving long-term sustainability. The updates serve as a reminder of the importance of commitment to environmental restoration and protection in the face of persistent issues.

In conclusion, the recent EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight the significant progress made in addressing contamination and restoring impacted communities. While strides have been achieved in cleanup efforts and remediation, ongoing challenges remain, emphasizing the need for sustained commitment and resources. Continued collaboration among stakeholders, including local communities and government agencies, will be vital in overcoming these hurdles and ensuring the long-term protection of public health and the environment in Massachusetts.

In conclusion, the recent updates from the EPA regarding Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in remediation efforts, demonstrating a commitment to improving environmental health and community safety. However, ongoing challenges remain, necessitating continued vigilance, funding, and stakeholder collaboration. The path forward will require an adaptive approach to address complex environmental issues while ensuring that affected communities remain informed and engaged in the rehabilitation process. As efforts continue, the importance of sustained federal and state support will be crucial in achieving long-term success and restoring these vital ecosystems.

In conclusion, the recent EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in the remediation and management of contaminated areas, reflecting the dedicated efforts of local, state, and federal agencies. However, the report also underscores ongoing challenges that require continued attention and resources to fully address remaining environmental concerns and ensure the safety of affected communities. As stakeholders work collaboratively to navigate these complexities, the commitment to restoring and revitalizing these sites remains crucial for public health and environmental resilience in Massachusetts.

In conclusion, the latest updates from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regarding Superfund sites in Massachusetts highlight significant progress in remediation efforts, reflecting the commitment to restoring affected areas. However, ongoing challenges remain, necessitating continued attention and resources to ensure the health and safety of communities. The dedication to addressing these complex environmental issues underscores the importance of collaborative efforts between federal, state, and local stakeholders in achieving sustainable solutions for a cleaner future.

In conclusion, the EPA’s updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites reflect a significant commitment to environmental remediation and public health, showcasing both notable progress in cleaning up contaminated areas and ongoing challenges that still need to be addressed. As efforts continue to mitigate the impacts of pollution, it is essential for stakeholders, including local communities and government agencies, to collaborate and ensure sustained advancements in revitalizing these sites. Ongoing vigilance and support will be crucial in overcoming the hurdles that remain and in fostering a healthier and safer environment for all Massachusetts residents.

In summary, the recent EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in addressing contamination and restoring affected areas, reflecting a commitment to environmental health and community well-being. However, ongoing challenges remain, including the need for sustained investment and collaborative efforts to ensure comprehensive remediation. As stakeholders continue to navigate these complex issues, the evolution of Superfund sites in Massachusetts serves as a critical reminder of the importance of vigilance and proactive measures in environmental stewardship.

In conclusion, the latest EPA updates regarding Massachusetts Superfund sites reflect significant progress in addressing environmental contamination and safeguarding public health. Continued efforts highlight the commitment to restoring affected areas and mitigating risks. However, ongoing challenges such as complex site conditions and funding limitations underscore the need for sustained collaboration among federal, state, and local stakeholders. As remediation efforts advance, it is crucial to maintain momentum and ensure that the success achieved thus far translates into lasting solutions for communities impacted by pollution.

In conclusion, the recent EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in the remediation and management of contaminated areas, demonstrating the agency’s commitment to public health and environmental restoration. However, ongoing challenges remain, underscoring the need for continued vigilance, funding, and community engagement to ensure the successful completion of cleanup efforts. Collective action and sustained focus will be essential in overcoming these obstacles, ultimately leading to safer and healthier environments for the communities impacted by past industrial activities.

In conclusion, the recent updates from the EPA regarding Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in cleanup efforts and environmental restoration. However, they also underscore the ongoing challenges that remain, including the need for continued funding, community engagement, and comprehensive monitoring. While strides have been made toward mitigating contamination and ensuring public safety, sustained efforts will be crucial to fully address the complexities of these sites and to protect both the environment and the health of local communities.

In conclusion, the latest EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in remediation efforts and environmental restoration. However, challenges remain in fully addressing contamination and ensuring long-term safety for communities. Continued commitment from both federal and state agencies, along with local stakeholders, will be crucial in overcoming these hurdles to protect public health and the environment in the region.

In conclusion, the recent updates from the EPA regarding Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight a significant commitment to environmental remediation and public health. While progress has been made in addressing contamination and restoring affected areas, ongoing challenges remain, underscoring the need for continued vigilance and investment in cleanup efforts. The collaborative approach between federal and state agencies, along with community involvement, will be crucial to ensure sustainable solutions and foster a healthier environment for all residents.

In conclusion, the latest EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in the remediation and revitalization efforts, reflecting a commitment to improving environmental health and community safety. However, ongoing challenges remain, necessitating continued vigilance and collaboration among federal, state, and local stakeholders. As efforts advance, it is crucial to maintain transparency and engage communities to ensure that the restoration of these sites benefits all residents and fosters sustainable development in the region.

In conclusion, the latest EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in the remediation and restoration efforts, demonstrating a commitment to environmental health and community revitalization. However, ongoing challenges indicate that the journey towards full recovery is far from over. Continued collaboration among federal, state, and local stakeholders will be essential to address these complexities and ensure the safety and sustainability of the affected areas for future generations.

In conclusion, the recent EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight a mixture of significant progress in remediation efforts and the persistent challenges that remain. While advancements in cleanup initiatives reflect a commitment to restoring contaminated sites and protecting public health, ongoing environmental complexities and funding issues underscore the need for continued vigilance and collaboration among federal, state, and local stakeholders. As these efforts move forward, it is crucial to maintain momentum and address the remaining challenges to ensure sustainable environments for Massachusetts communities.

In conclusion, the recent updates from the EPA regarding Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in remediation efforts, reflecting a commitment to environmental health and community well-being. However, ongoing challenges remain that require continued vigilance, funding, and stakeholder collaboration to ensure that these contaminated sites are addressed effectively. As Massachusetts moves forward, it is crucial to maintain focus on both overcoming these challenges and building upon the successes achieved thus far, ultimately aiming for a safer and cleaner environment for all residents.

In conclusion, the EPA’s latest updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites reflect a positive trajectory in cleanup efforts, demonstrating significant progress in mitigating environmental hazards and safeguarding public health. However, ongoing challenges remain, underscoring the need for continued vigilance, funding, and community engagement to address remaining contaminants and ensure the long-term health of affected ecosystems and residents. As stakeholders work collaboratively, it is essential to maintain momentum and commitment to fully restore these critical sites to safe and productive uses.

In conclusion, the recent EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in remediation efforts, reflecting a commitment to restoring contaminated environments for public health and safety. However, the reports also underscore ongoing challenges, including the complexity of site cleanups and the need for sustained funding and community involvement. As these efforts continue, collaboration among state, federal, and local stakeholders will be crucial in overcoming barriers and ensuring the long-term success of Superfund initiatives in Massachusetts.

In conclusion, the recent updates from the EPA regarding Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in remediation efforts, reflecting a commitment to environmental restoration and public health. However, ongoing challenges remain, necessitating continued vigilance and resource allocation to address lingering contamination issues and community concerns. As stakeholders work collaboratively to navigate these complexities, the pathway toward fully rehabilitated ecosystems and safer communities is both a priority and a shared responsibility.

In conclusion, the recent EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in remediation efforts and the ongoing challenges that remain. While many sites have seen improvements that promise a safer environment for local communities, the continuous monitoring and commitment to addressing contamination issues remain critical. These updates underscore the importance of collaboration among governmental agencies, local stakeholders, and the public to ensure sustainable recovery and protection of human health and the environment in the future.

In conclusion, the EPA’s recent updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in the remediation and restoration of contaminated areas, reflecting the commitment to protecting public health and the environment. However, the reports also underscore ongoing challenges that remain, emphasizing the need for sustained effort, adequate funding, and community involvement to address complex contamination issues. As the state continues to navigate these challenges, the collaboration between federal, state, and local agencies will be crucial in ensuring a safer and cleaner future for affected communities.

In conclusion, the recent updates from the EPA regarding Superfund sites in Massachusetts highlight both significant strides in remediation and the continuous hurdles that remain. While progress is evident in the cleanup and restoration efforts, challenges such as funding, regulatory complexities, and community involvement underscore the need for ongoing commitment and collaboration. These updates serve as a reminder of the importance of environmental stewardship and the necessity for sustained action to ensure safe, healthy communities for all residents in the impacted areas.

In conclusion, the recent updates from the EPA regarding Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight important strides made in remediation and environmental protection efforts. While progress is evident in addressing contaminated sites, ongoing challenges remain that demand continued attention and resources. The commitment to safeguarding public health and the environment underscores the need for collaborative efforts among federal, state, and local stakeholders to ensure that these sites are thoroughly managed and rehabilitated, paving the way for safer communities and sustainable ecosystems.

In conclusion, the latest EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in the cleanup and management of contaminated areas, reflecting a committed effort to safeguard public health and the environment. However, ongoing challenges remain, underscoring the need for continuous monitoring, funding, and community engagement. The commitment to addressing these challenges will be crucial in ensuring the long-term effectiveness of remediation efforts and the restoration of these vital ecosystems.

In conclusion, the recent EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in cleanup efforts and site management, reflecting a commitment to improving environmental and public health. However, ongoing challenges remain, underscoring the need for continued vigilance and investment in remediation efforts. As stakeholders work collaboratively to address these challenges, the updates serve as a reminder of the importance of community engagement and sustainable practices in ensuring the long-term success of Superfund initiatives.

In conclusion, the recent EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in remediation efforts and the commitment to restoring affected areas. However, ongoing challenges remain, emphasizing the need for continued vigilance and collaboration among stakeholders. As these efforts advance, they not only aim to mitigate environmental hazards but also to enhance public health and community resilience, underscoring the importance of sustained investment and attention to these critical sites.

In conclusion, the recent EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in the cleanup and management of contaminated areas, reflecting the dedication of federal and state agencies to restore these environments. However, ongoing challenges remain, necessitating continued vigilance and investment to address remaining hazards and ensure the health and safety of affected communities. The commitment to these efforts underscores the importance of collaboration between government entities, local stakeholders, and the public in achieving lasting solutions for environmental remediation.

In conclusion, the latest EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in remediation efforts, reflecting a commitment to improving environmental health and community safety. However, ongoing challenges remain, necessitating continued vigilance and investment to address lingering contamination and protect public health. Collaborative efforts among federal, state, and local stakeholders will be essential to overcome these hurdles and ensure the successful revitalization of impacted areas for future generations.

In conclusion, the recent EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in addressing contamination and restoring impacted environments. However, ongoing challenges remain, underscoring the complexity of environmental remediation efforts. Continued collaboration among federal, state, and local stakeholders will be essential to navigate these challenges and achieve lasting solutions for the affected communities. The commitment to monitoring and improving these sites reflects a dedication to public health and ecological restoration, emphasizing the importance of sustained efforts in environmental protection.

In conclusion, the recent updates from the EPA regarding Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight both significant progress and persistent challenges in the remediation process. While advancements have been made in addressing contamination and restoring affected areas, ongoing issues underscore the need for continued vigilance and investment in environmental protection efforts. Stakeholders must collaborate to ensure that these sites are fully rehabilitated to safeguard public health and preserve the environment for future generations.

In conclusion, the latest EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites demonstrate significant progress in remediation efforts, reflecting a commitment to environmental restoration and community health. However, ongoing challenges highlight the complexity of addressing contamination issues, underscoring the need for continued collaboration and resource allocation. As stakeholders work together to overcome these hurdles, the path to a cleaner, safer environment continues to evolve, showcasing both achievements and the necessity for sustained vigilance and action.

The recent EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in the remediation of contaminated environments, reflecting a strong commitment to restoring public health and ecological balance. However, ongoing challenges remain, including the complexity of certain sites, funding limitations, and community engagement in decision-making processes. Continuous efforts and collaboration among federal, state, and local stakeholders will be crucial in overcoming these hurdles and ensuring the long-term success of Superfund initiatives in Massachusetts.

In conclusion, the latest EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant advancements in the remediation and management of contaminated areas, demonstrating a commitment to protecting public health and the environment. However, ongoing challenges remain, underscoring the need for continued vigilance, funding, and community engagement to address the complexities of contamination and ensure that all sites are remediated effectively. The commitment to progress in these efforts is vital for fostering a safer, cleaner, and more sustainable future for Massachusetts residents.

In conclusion, the recent updates from the EPA regarding Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in the ongoing efforts to remediate these contaminated areas. While strides have been made in cleaning up hazardous waste and protecting public health, the challenges that remain underscore the complexity of environmental restoration. Continued collaboration among stakeholders and sustained commitment to addressing these issues will be essential to ensure that all affected communities can thrive in a cleaner, safer environment.

In conclusion, the recent EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in addressing environmental contamination and restoring affected areas. However, ongoing challenges remain, underscoring the need for continued commitment and collaboration among stakeholders to ensure the long-term health and safety of communities. As efforts persist, it is essential to maintain transparency and public engagement to foster trust and support for these critical remediation initiatives.

In conclusion, the recent updates from the EPA regarding Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in remediation and environmental restoration efforts. However, ongoing challenges remain, underscoring the need for continued commitment and collaboration among state and federal agencies, local communities, and stakeholders. As efforts advance, it is essential to maintain transparency and prioritize public health to ensure that these areas are not only cleaned up but also safeguarded for future generations. The path forward may be complex, but the strides made thus far demonstrate a dedicated pursuit of environmental justice and sustainability.

In conclusion, the EPA’s recent updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight significant progress in addressing longstanding environmental concerns, showcasing effective remediation efforts and collaborative initiatives. However, ongoing challenges remain, underscoring the need for continued vigilance, funding, and community engagement to ensure the safety and health of affected areas. As we move forward, it is essential to maintain a committed approach to these projects to achieve lasting solutions and safeguard the environment for future generations.

In conclusion, the recent updates from the EPA regarding Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight a positive trajectory in environmental remediation and public health improvement. While significant progress has been made in mitigating contamination and restoring affected areas, ongoing challenges remain that require continued attention and resources. Collaborative efforts among federal, state, and local agencies, alongside community involvement, are essential to address these challenges and ensure that Massachusetts can achieve long-term environmental safety and sustainability.

In conclusion, the recent EPA updates on Massachusetts Superfund sites highlight a significant commitment to environmental restoration and public health. While progress has been made in addressing contamination and mitigating risks in affected areas, ongoing challenges remain that require continued attention and resources. Collaborative efforts among federal, state, and local stakeholders are essential to ensure that these sites are remediated effectively and that the communities impacted can move towards a sustainable and healthy future.